Both Thangka painting and Mandala stand as luminous pillars of Himalayan Buddhist visual culture — two languages of the sacred, each speaking to the same truth through a different form. To the untrained eye, both may appear as intricate, meditative art forms filled with divine figures and cosmic geometry. Yet for the practitioner, their purposes diverge profoundly.

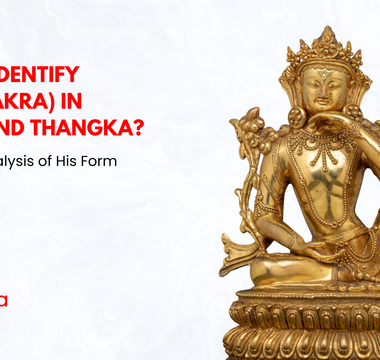

A Thangka painting is a piece of art; it is a portable altar, a rectangular window into realms of compassion and enlightenment. Within its borders lives a deity, teacher, or sacred narrative, rendered with meticulous precision so that the practitioner can engage in devotional visualization. When one meditates on a Thangka, one gazes into the eyes of the divine — the painting becomes a mirror that reflects the awakened state within oneself. Its purpose is personal, relational, and emotional: to invoke presence, devotion, and spiritual intimacy.

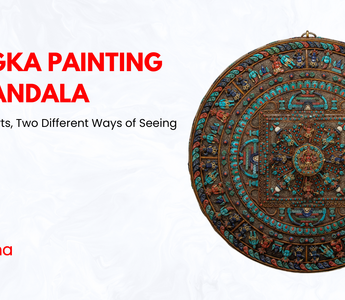

In contrast, a Mandala painting is a cosmogram — a precise, geometric map of the universe and the awakened mind. Instead of depicting a single divine figure, it represents the architecture of enlightenment itself: a sacred palace built from symmetry, color, and proportion. The practitioner does not simply look at the Mandala; they enter it through meditation, journeying inward from the outer circles of worldly illusion to the radiant center of truth. The Mandala is not a portrait of divinity — it is the blueprint of awakening.

Mandala Wall Art with Eight Auspicious Symbols

Understanding this difference matters because it reveals the two complementary approaches of Vajrayana Buddhism:

-

Thangka evokes devotion and relationship — the outer form of divine presence.

-

Mandala embodies structure and realization — the inner geometry of liberation.

Together, they illustrate how the visual arts of Vajrayana are not decorative expressions but spiritual technologies — tools to train the eye, the mind, and the heart toward awakening.

What is a Thangka painting?

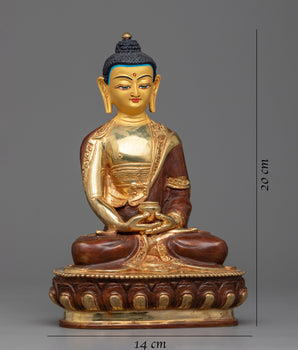

A Thangka is a Tibetan hanging scroll painted on cotton or silk, traditionally mounted in silk brocade and kept rolled when not in use—portable, liturgical, and designed for viewing in ritual contexts.

Subjects and Iconometry: Thangkas predominantly depict Buddhas, bodhisattvas, lineage teachers, protectors, and occasionally narrative cycles. The aim is devotional: the image is a support for visualization and merit-making.

Thangka painting follows strict iconometric canons—proportions and attributes are codified in manuals to ensure doctrinal accuracy. This is a process-oriented, rigorous craft with defined steps (ground preparation, grid and measurements, underdrawing, mineral pigments, gilding, mounting).

Read more about Thangka painting and its Types

What is a Mandala?

A Mandala is a geometric configuration—often a circle with an inner square “palace”—that represents the cosmos and the deity’s abode, complete with gates, directional colors, and retinues. It’s a highly technical diagram used in tantric practice.

Function in practice. Practitioners visualize entering the mandala palace and moving from the outer rings to the center, a journey mapping the transformation of perception toward the awakened state. Monastic sources emphasize that it is a tool for guiding one along the path to enlightenment, often imagined as 3D.

Side-by-Side: Comparing The Differences

| Dimension | Thangka Painting | Mandala Painting |

|---|---|---|

| Primary role | Devotional image (deity/teacher/scene) for visualization and teaching | Cosmogram (sacred plan) for meditative entry and tantric ritual |

| Typical format | Rectangular hanging scroll on cloth; silk brocade mount; rolled when stored | Circular plan with square palace; geometric layout with gates and concentric bands |

| Focus of attention | The personified presence—meeting the deity’s gaze, cultivating qualities | The journey into structure—moving inward to the center (awakening) |

| Rule system | Iconometric canons (proportions, attributes) for correct depiction | Canonical layouts (directions, colors, retinues, implements) for correct cosmology |

| Media | Pigments on cotton/silk, sometimes appliqué; mounted in silk brocade | Pigments on cloth, sand, bronze/metal, and 3D models |

| Ritual lifecycle | Durable, conserved, displayed for ritual/festival use | Often temporary (sand) with ritual dissolution to enact impermanence |

| Pedagogical effect | Teaches via presence & narrative | Teaches via space, order, and process |

Sources for the table: Rubin Museum (Thangka definitions, process)

Technique & workflow: where painters diverge

Thangka painting workflow

-

Sized cloth & ground (gelatin/animal glue + chalk) to create a smooth painting surface.

-

Grid & iconometry: artists lay out the figure using proportional canons.

-

Underdrawing and mineral pigments (often with precise layering and shading), gilding, outlining, and final consecration.

-

Mounting in silk brocade, with top/bottom dowels; stored rolled.

The accuracy of proportions and attributes matters doctrinally; the image is not merely aesthetic but ritually effective because it is correct. Source: Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art

Mandala workflow:

Sand Mandala Making Process: photo by Tibet Vista

-

Geometric scaffolding: concentric rings, square palace with four gates, directional coding.

-

Placement of deities by quadrant/axis according to tantric manuals and lineage instructions.

-

Color logic & symbolism (elements, directions, buddha-families).

-

In sand mandalas: ceremonial site consecration, meticulous sand application using chak-pur funnels, and closing dissolution (swept up, sand poured into water).

The process is a practice environment; the real “image” is the process of entry and dissolution, not permanence.

Conclusion

Thangka painting is a devotional portrait and narrative vehicle—a way to meet awakened presence through color and form while Mandala is a cosmic diagram and practice environment—a way to enter awakened structure by moving from circumference to center.

Distinct in format, technique, and ritual life, both share a single aim: to train attention and transform perception—turning looking into practice.