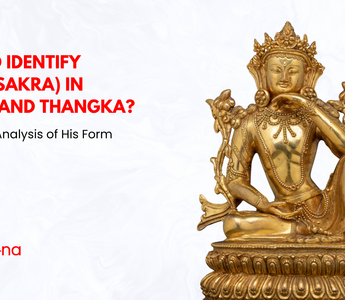

Introduction: Who Is Indra?

Indra — the King of the Gods in Hindu mythology — rules over rain, thunder, and the heavens. Known as Devaraja and Lord of Svarga, he is one of the most ancient and dynamic deities in the Vedic pantheon.

But how do you recognize Indra in a temple carving, bronze statue, or Buddhist/Jain motif? His depictions vary across regions and traditions. This guide will help you identify Indra accurately, explore his symbols, and understand their spiritual meaning. Read more about Lord Indra:

Main Features of Indra (Śakra) in Buddhist Art

1) Vajra (Kongō) — how it looks in Buddhist contexts

-

Form & grip: In Indian/Himalayan Buddhist art Śakra’s vajra is often multi-pronged and may be resting on a lotus stalk by his shoulder rather than raised for combat — a ceremonial, restrained power cue.

-

East Asia (Taishakuten): In Japanese esoteric imagery he can hold a single-pronged kongō (vajra) and appear as a martial guardian. Buddhistdoor

-

Distinguish from Vajrapāṇi: If the figure is wrathful, muscular, and emphatically guardian-like, consider Vajrapāṇi instead; Śakra’s mien is typically regal/celestial, not wrathful. (Background on vajra vs. Vajrapāṇi for contrast.)

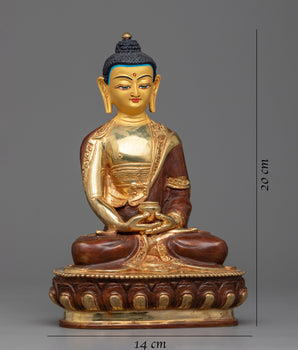

2. Royal regalia & posture (Buddhist court style)

-

Crown & jewels: Himalayan Buddhist sources note a broad, fan-shaped crown, abundant jewelry, and a lotus-borne vajra by the left shoulder. These are reliable Śakra identifiers in Nepal/Tibet.

-

Third eye (Himalayan cue): A horizontal third eye may appear on the forehead in Himalayan Buddhist depictions — a niche but distinctive identifier recorded in museum/iconography sets.

-

Demeanor: Śakra reads as regal/benign (king of the Trāyastriṃśa gods), not wrathful; stances are samabhanga (upright) or lalitāsana (royal ease).

Śakra (Indra) in Buddhist Narratives & Cosmology — What to Look For

1) Descent from Trāyastriṃśa Heaven (Devāvatāra/Devorohaṇa)

After teaching his mother in Trāyastriṃśa, the Buddha descends to earth by a miraculous triple staircase.

Indra descends alongside the Buddha and Brahmā, each on their own flanking stairway. Śakra is typically on one side (often the “crystal/silver” stair in textual retellings), wearing celestial regalia; Brahmā is on the other.

How to spot him:

-

A turbaned or crowned celestial to the Buddha’s side on the stairs.

-

Courtly pose (not wrathful), sometimes with an attendant retinue.

-

If attributes are faint, rely on the paired presence with Brahmā and their symmetric flanking of the Buddha.

photo Credit: Enlightenment Thangka

2) Visit to the Indraśailā (Indrasāla) Cave

Śakra visits the meditating Buddha in a cave; Pañcaśikha (the Gandharva) plays music to introduce Śakra’s questions (the Sakkapañha Sutta, Dīgha Nikāya II.21).

A royal, jeweled deva approaching or seated near the cave, sometimes with Pañcaśikha and a stringed instrument; in Gandhāran reliefs, Śakra may be signaled by an elephant nearby or by his dignified court costume.

How to spot him:

-

Cave setting with the Buddha inside/on a rocky ledge.

-

A celestial visitor in regal attire; look for the musician (Pañcaśikha) as a narrative anchor.

-

In some panels, Śakra’s elephant (Airāvata/Erāvana) appears to the side.

Where this shows up: From early Bodhgayā/Māthura to Gandhāra and later SE Asian reliefs and murals; encyclopedic entries summarize the iconography and give dated examples.

3) Wheel of Life (Bhavacakra) — Realm of the Gods

The six realms arranged in sectors; the gods’ realm sits at the top.

Within the gods’ palace, Śakra plays a stringed instrument—a didactic motif that underscores the pleasures (and impermanence) of the deva realm.

How to spot him:

-

At the top sector, a celestial king (seated comfortably, serene)

-

Tibetan/Himalayan thangkas and wall charts; curatorial pages explicitly identify the player as Śakra (Indra).

4) Theravāda Southeast Asia — Sakka in Jātaka Cycles & as Guardian

In narratives like the Vessantara Jātaka, Sakka intervenes to test, aid, or reward protagonists. In Burmese/Thai art he also appears as a guardian near entrances or in didactic murals.

Labeled inscriptions (“Sakka”), royal headdress, and sometimes a small vajra/kongō or elephant in the composition.

How to spot him:

-

As a guardian, he can appear enthroned or hovering with parasol/attendants.

Where this shows up: 18th–19th c. Thai/Burmese cloths and murals; museum records tag the figure explicitly as Sakka (Indra) in Vessantara scenes.

5) Japan — Taishakuten in the Twelve Devas (Jūniten) & Esoteric Mandalas

Taishakuten appears among the Twelve Devas (protectors of directions/realms) and within Shingon/Tendai mandalas and temple cycles, often paired near Bonten (Brahmā).

Śakra’s cue: A dignified martial/celestial figure holding a kongō (vajra); sometimes shown seated on an elephant. Courtly armor and tall headdress are common.

How to spot him:

-

Group portraits of the Twelve Devas in paintings/screens; identify by kongō and elephant seat (when present).

-

In ritual iconography, he’s the ruler of Trāyastriṃśa (Jp. Tōriten) and commander of the Four Heavenly Kings—so the pose may be authoritative but not wrathful.

Where this shows up: Japanese temple cycles from Heian onward; reference entries and iconography essays summarize the set and Taishakuten’s attributes.