Tibetan Buddhism is rich in myth, symbolism, and visual art. Among the most fascinating, and sometimes misunderstood, creatures in its cosmology is the dragon. Unlike Western dragons, Tibetan dragons carry meanings that are deeply spiritual, symbolic, protective—and they appear in many forms: in myth, in ritual, in thangkas and statues, and even in national identity. In this article we'll explore:

-

What “dragons” mean in Tibetan Buddhism, how they are distinguished from related beings like nāgas

-

Which deities are depicted riding dragons or associated with them

-

How dragons are represented in Tibetan art—thangka paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, ritual objects etc.

-

Their symbolic roles: guardianship, power, wisdom, weather, auspiciousness

Dragon motif on Shakyamuni Buddha Thangka: click here to View

Defining “Dragon” in the Tibetan Buddhist Context

Dragon vs. Nāga (serpent)

One frequent confusion is between dragons (in Tibetan druk, drug, zhu, etc.) and nāgas. Nāgas are serpent-or dragon-like beings, usually water-spirits or subterranean/underwater entities in Indian and Buddhist traditions. They often guard treasures or sacred texts, can be beneficent or malevolent, and are deeply tied to water, fertility, and the hidden powers of the earth.

Dragons, in the Tibetan context, often have different connotations: primordial power, thunder, sky elements, guardianship, symbolism of wisdom, auspiciousness, and especially as one of the “Four Dignities” (alongside Garuda, Snow Lion, Tiger).

It’s also important: in Tibetan art, dragons often fly without wings, have horns, claws, sometimes jewels in their jaws or claws, sometimes multiple heads, tongues of flame etc. These features distinguish them visually from simpler serpent forms (nāgas).

Symbolic Meanings of Dragons in Tibetan Buddhism

-

Primordial Power & Veneration of Nature

The dragon is often an embodiment of elemental power—wind, thunder, storm, water. In Tibet, where climate is harsh, where the elements are respected, dragons are seen as beings who govern rivers, lakes, rain, weather phenomena. They are respected (and propitiated) because they can bring drought or flood. -

Guardians of the Dharma & Wisdom

Dragons are sometimes protectors of sacred texts, teachings, places. Their fierce roar can “wake beings from delusion”. They sometimes act like guardians (dharmapalas) symbolically. -

Auspiciousness, Wealth, Prosperity

In Tibetan culture dragons bring good fortune. They are decorative on important sacred objects, prayer flags, furniture, Thangkas, facades etc.: they embellish and confer auspiciousness. Also associated with wealth deities riding dragons elevate the symbolism. -

Cosmic & Directional Symbolism

Dragons are one of the Four Dignities: dragon (east or other directions depending on tradition), garuda, snow lion, tiger. On prayer flags, temple decorations etc., these four are placed in each of the four cardinal directions to represent protection of the cosmos, well-being, stability.

Iconographic Features: What Do These Dragons Look Like?

Some common visual features of Tibetan dragons include:

-

Four legs, clawed; sometimes multiple heads (9, etc.) in special cases.

-

No wings, yet capable of flight. Movement is often implied with cloud, flame, wind, trailing whiskers.

-

Horns or antlers on their head, often deer-type or curved horns.

-

Jewel or pearl in forehead or in claws (“wish-fulfilling jewel”) symbolizing spiritual wealth, clarity, or auspicious power.

-

Elaborate scales, long serpentine body, tail curling, expressive (open mouth, tongue or flames). Colors vary: blues, greens, turquoise, sometimes gold or red.

-

Surrounded by cloud or flame motifs; in many paintings, the dragon is drawn interacting with its element (rain, water, wind)

Deities Who Ride Dragons & Dragon-Mounts in Tibetan Buddhist Art

“Mounts” means the creature a deity sits or rides upon in iconography, an important part of depicting their attributes and powers. Some deities are explicitly shown riding dragons, or with dragons associated. Here are several examples:

| Deity / Protector | Tradition / Lineage | Dragon Mount / Association |

|---|---|---|

| White Jambhala (Wealth Deity) | In Himalayan / Tibetan art | Depicted riding a turquoise-coloured dragon, accompanied by dakinis. This emphasizes his dominion over wealth, prosperity, and connection with elemental powers. Himalayan Art Resources |

| Rahula | Nyingma protector from the Revealed Treasure (terma) Tradition of Dudul Dorje | Mounted atop a dragon in some thangka iconography. |

| Tashi Tseringma with her four sisters | Kagyu tradition | One of her forms (‘Tekar Drozangma’) is shown riding a blue dragon which also clutches wish-fulfilling jewels in its claws. Himalayan Art Resources |

| Nujin Shan Mar | Yutog Nyingtig (terma lineage) | She rides atop a dragon sometimes depicted with nine heads. Himalayan Art Resources |

These are not exhaustive, but they show that the dragon is not only a decorative motif but an active symbol of divine energy, of protection, often entrusted to deities whose role is to confer tangible benefit (prosperity, protection from harm, obstacles) or spiritual protection.

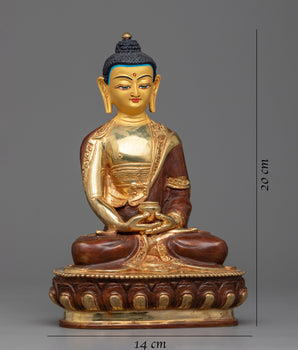

White Jambala Riding a Dragon: click here to view the Statue

Appearance of Dragons in Thangka/Sculpture and Artforms

Thangka Paintings

-

Borders / Torana Backdrops: Dragons often appear as part of decorative borders or the torana (doorway /arch) behind the throne of a deity. From about the 18th century onward these decorative dragon papers or painted motifs become more common.

-

Mounts of Deities: As in the table above, mounted deities are shown perched on dragon-mounts. These tend to be very colorful: turquoise, blue, sometimes green or mixed, with flame or cloud motifs around them.

-

Depiction of Dragons in Narrative Scenes or Sūtra Illustrations: Scenes like the Dragon King of the sea offering to the Buddha, or nāga-dragon kinds, appear in sūtra illustrations. Also sometimes dragons appear in contexts of mythic stories—e.g. battles, or cosmic events.

Sculptures & Architectural Ornamentation

-

In some temple facades, rooflines, ritual objects (such as handles, vajra decorations, hinges etc.), dragons are carved, gilded, or painted. Their forms often curl, coil, with stylized scales, horns, expressive faces with open mouths, breath or flame.

-

Statues of mounted deities: in three-dimensional sculptures, the mount may be a dragon. The dragon becomes part of the statue (e.g., deity riding atop a richly modeled sinuous dragon, dragon’s claws, body visible etc.)

Click here to view our Dragon home Decor

Manuscripts & Books

-

Manuscripts can be lavishly illustrated, especially special commissioned Buddhists canons. One famous example: the Tibetan Dragon Buddhist Canon (Kangyur), written in gold ink on Tibetan blue paper, with binding covers embroidered with dragon imagery. The decorative bindings often include coiled dragons, motifs in the wrap silk, protective cover planks with dragon embroideries. The term “Dragon Canon” itself reflects the role of dragons as guardians and symbol of sacredness.

More detailed article on Google Arts & Culture -

The covers of sacred texts often have protective motifs; dragon imagery serves to protect the text (the teachings) much as they protect deities and places.

Examples of Art & Mythic Incarnations

-

Four Directional Dignities: In many Tibetan prayer flags and Buddhist compositions, the dragon is placed among the four dignities, often in upper corners, balancing other symbolic animals. As with the wind horse (lungta) design where dragon appears in upper corners.

-

White Jambhala riding dragon (as noted) is an example of wealth deity given power and mobility through a dragon mount.

-

Torana throne decorations: The arch or halo behind deities may include dragons in the decorative design, sometimes at the top, coiled or in flight. These are sometimes later additions, reflecting cultural influences (Chinese style etc.)

Role in Ritual, Belief, and Culture

-

Weather & Rain: Because dragons are associated with rain, thunder, storms, they become invoked in rituals for good weather, fertility, agriculture. Their benevolence in such contexts is essential for Himalayan agrarian life.

-

Protection: Protective deities often use dragon imagery or ride dragons to denote their power to overcome obstacles. Also, dragon symbols at gates, roof ridges etc. serve protective function.

-

Symbolic Awakening: Some texts and teachings treat the roaring of the dragon as symbolic of awakening the mind from delusion, making the practitioner vigilant. The dragon is less of a monster and more a powerful ally in spiritual practice.

-

Identity & National/Lineage Symbol:

-

Druk / Drukpa: The “Thunder Dragon” (Druk) is central to the Drukpa lineage, and Bhutan is “the land of Druk”, “Druk Yul”. Bhutan’s flag bears a dragon clutching jewels, symbolizing wealth and national guardianship.

-

Lineage-symbols, monastery names, insignias often use dragon imagery, horned dragon hats, etc.

-

Historical & Cultural Origins & Cross-Cultural Influences

-

Tibetan dragons appear to come partly from Indian nāga tradition, partly through contact with Chinese culture. Art motifs of Chinese dragons influenced Tibetan decorative elements from around 15th century onward. Some of the decorative appearances of dragons in thangkas, manuscripts, ornamentation are linked to that contact.

-

The use of dragons as mounts is less in early Tibetan art, more common after later centuries, particularly when monastery patronage and influences of decorative styles increased.

Dragons in Tibetan Buddhism are not just mythical beings; they are living symbols. They remind practitioners of the power of awakened awareness (thunder, wind, roar), of the need to protect what is sacred, to invite auspiciousness, to awaken from ignorance. For the lay practitioner: recognizing dragon imagery in temples, prayer flags, thangkas invites mindfulness of one’s environment, connection with nature, awareness of the unseen. For artists and practitioners: the accurate depiction of dragons—its attributes, colors, context—is more than decorative; it's part of sacred iconography, meant to embody aspects of meaning.

Through art—thangka, sculpture, manuscripts—and through myth and ritual, dragons remind practitioners of the power of awakening, protection, and interconnection with nature.

If you walk into a temple and see a deity riding a dragon, it’s more than a pretty image: it’s a statement that this deity holds power over elements, bestows blessings, guards the teachings. Recognizing that helps deepen one’s appreciation—both spiritual and aesthetic—for Tibetan Buddhist art and practice.