Two Cultures, One Spirit: A Journey Through Paubha and Thangka Art

Paubha Art and the Tibetan Thangka in the Himalayas which is not merely an expression of aesthetics but also sacred, symbolic, and transformative, as seen in the artworks. While they share iconographical traditions, they differ significantly in cultural origins, spiritual philosophies, and artistic practices. They have historically served as portable temples, places for meditation, and essentially as visual and written texts. Each line, symbol, and color has a meaning created by the heart, rooted in centuries-old rituals and religious disciplines. Paubha paintings, steeped in the Newar Buddhist and Hindu practices of the Kathmandu Valley, complemented by the Tibetan Thangka tradition, offer a deeper understanding of the larger spiritual cosmos represented in Tibetan Buddhism. Recognizing differences means we can move into the unique views, rituals, and aesthetic practices of their own culture, and ultimately see these works of art as living traditions that tell the stories of each culture through their sacred brushstrokes.

What Is Paubha and Thangka Art?

Click Here To View Our Avalokitesvara, A Masterpiece of Paubha Art

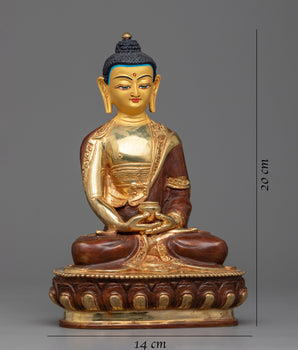

Paubha, also known as Beri/Newari painting, is a sacred painting tradition from Nepal created by the Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley. Often depicted on cloth, these images feature Buddhist and Hindu deities and are used for worship, meditation, and other rituals. Renowned for their fine line work, earthy colors, and extensive spiritual meanings, they seamlessly blend the traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism into a distinctive and recognizable Newari style.

A Thangka is a Tibetan Buddhist scroll painting. These paintings, created on cloth or silk, are used as part of rituals, meditation practices, and teachings, and generally depict Buddhas, deities, mandalas, or spiritual teachers. Tibetan artwork is movable, often framed in silk, and follows strict religious iconography. They are a valuable source for instruction or contemplation, and many are found in both monastery and home settings. They are primarily an essential part of rituals practiced in Vajrayana Buddhism.

The Origins and Spiritual Meaning of Paubha and Thangka

1. Paubha: The Sacred Art of the Newar People

Paubha painting has a unique history spanning nearly a thousand years. Still, one of its best-recorded periods is around the 11th century, with possible origins dating back to the Lichhavi period (400-750 CE). The word “Pauba” derives from the Sanskrit word pata, meaning "cloth," and refers to the medium used by most of these religiously related artists for their works, paintings on cloth or canvas. During the 14th through 15th centuries CE, Paubha painting was the dominant style of painting in Tibet, illustrating the influence of Nepali art on Tibetan culture. Steve Kossak's article, "Vasudhara Mandala," mentions that the earliest surviving Paubha picture, which dates back to 1367 CE, was created at a time when Muslim attacks on the Kathmandu Valley destroyed numerous historic artworks.

Paubha is exclusively found in Nepal and holds paramount importance in the religious and cultural lives of the Newar people in the Kathmandu Valley. The Newars are known for their decorative items, and can be seen in minor figures that are at once both Buddhist and Hindu. The paintings in the Hindu tradition often feature many Buddhist figures, including Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Dhyani Buddhas, while Hindu figures typically include Shiva, Vishnu, and Lakshmi. They do not exist in a vacuum, and iconography representing both traditions is woven together and coexists. The Traditional Newar painting can thus be characterized as a syncretic or inclusive form of art.

Newar Culture and Spiritual Meaning

In Newar society, Paubha is not just art but a sacred representation that is worshiped. Therefore, in Newar society, these paintings hold great importance in the realm of religious life and ritual, and are often displayed in public areas of worship, such as temples, monasteries, and private homes. One of the more prominent examples of traditional art use and display coincides with Gunla, the sacred month for Buddhists or followers of the faith, during which they conduct pilgrimages, attend ritual prayer services, and venerate, accompanied by devotional music and offerings.

In Newar society, every Paubha serves a meditative function, as each features a central deity that serves as a focal point for meditation, prayer, and inward transformation. For Newars, producing or displaying an artwork representation is a noble act that earns spiritual merit, as it is believed to invite divine blessings, provide spiritual protection, and promote group harmony. Newari Art is not only described as a means of individual devotion but also as the universal intercession between the divine realm and the human realm.

2. Thangka: The Visual Scripture of Tibetan Buddhism

Thangka, also known as Tangka or Thanka, originated around the 7th to 9th centuries CE. It was developed from its roots in Paubha, which remained an essential tradition in Nepalese Newar art. However, it also charted a course of development for Thangka in Tibet, just over the border in the Himalayan culture. The practice of Tibetan painting developed both monastically and lay, and has notable portable dimensions. As Tibetan Buddhism developed its own uniquely Buddhist aspects over hundreds of years, it evolved into a more uniform product with rich symbolism, reflecting the real practice of Buddhism as a Tantra within Vajrayana.

The typical Thangka presents Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and other Tantric deities, as well as protectors, mandalas, and cosmological aspects, such as stories from the life of a great teacher (Lama). The artwork adheres to a clear iconographic convention for each element situated within a painting, as listed in sequence in centuries-old manuals for religious texts.

Spiritual Meaning in Tibetan Practice

When it comes to Tibetan culture, the spiritual meaning of Thangka cannot be overemphasized; it serves as a support in visualization practices, where the practitioner imagines themselves as the deity to cultivate the deity's qualities, such as compassion, wisdom, strength, or transcendence. In ceremonial contexts, the painting becomes a living representation of the deity, possessing the power to activate the space and shape the ceremony.

In Tibetan monasteries, enormous ceremonial Thangkas can be viewed during festivals such as Monlam or Saga Dawa, which attract thousands of devotees who come to be blessed. They are not limited to religious settings; they also serve as pictorial scriptures for conveying teachings, illustrating moral lessons, mapping cosmology, and guiding the path to enlightenment.

The Paubha Art Vs. Tibetan Thangka

Although Paubha and Thangka paintings may, on the surface, seem visually similar due to their detailed representations of deities, mandalas, and a variety of spiritual symbols, their differences are worth examining to appreciate their cultural origins fully. Each, from thematic to stylistic to usage to meaning, exemplifies the mindset and spiritual rhythms of the populations in which they arose.

|

Feature |

Paubha Art |

Thangka Art |

|

Origin |

Newar Buddhist community in Nepal |

Tibetan Buddhism |

|

Religious Context |

Hindu-Buddhist syncretism |

Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism |

|

Artistic Influence |

Nepalese style, indigenous; Pala art |

Heavily influenced by Indian and Chinese arts |

|

Color Palette |

Earth tones, pigmented color, and golds |

Bright, vivid colors |

|

Function |

Worship, meditation, public and household display |

Visualization, teaching, and tantric ritual |

|

Format |

Cloth/canvas, usually mounted but not framed |

Scroll format, framed with silk brocade |

|

Style |

More local elements like Nepalese motifs |

Global Buddhist symbolism |

|

Design |

Dense patterns, symmetrical layout |

Minimalist and organized layout |

|

Deities |

Hindu gods & Buddhist figures |

Buddhist figures, Lamas, protectors, mandalas |

The Shared Spirit of Paubha and Thangka Art

Paubha and Thangka are distinct art forms that evoke different cultural experiences; they share an essence of spirituality that connects them. These art forms are so much more than lovely images. They are meditative experiences visually, they are sacred texts, and enchanted spaces of enlightenment. Each brushstroke is purposeful, each color is understood; each figure holds significant spiritual meaning. Artists don't just paint; they engage with their devotion to their tradition. Many artists undergo a form of religious training to gain a deeper understanding of their art in context, which involves comprehending the iconographical elements, the process of creating the work, including the rituals, and the spiritual significance of their work.

When a Paubha or Thangka is created, it is also a form of meditation. The artist embarks on a process in which they enter a meditative/divine state of self-reflection, becoming focused and clear in thought, so that the image they create will become a representation of divinity, like a crystal-clear mirror. Similarly, they also serve as a form of meditation for the viewer; in the painting, there is more than just an image; it is a space where we can be invited to contemplate, meditate on, and be inwardly curious about the wisdom of the piece. The two traditions have a long history of being closely related. Many of the early Tibetan painters had Newar Paubha artists from Nepal come to medieval Tibet to teach them. A significant amount of experience influenced by Newar culture is reflected in the culmination of vocabulary in Tibetan Buddhist art. The inter-exchange established a shared artistic lineage, allowing for room to grow and develop their cultural expressions.

Preservation of Sacred Traditions of Paubha and Thangka Art

Paubha and Thangka painting traditions are still alive and well, but they are facing immense challenges. In this era of rapid modernization, ancient practices are threatened by emerging challenges stemming from commercialization, the erosion of traditional mentorship, and cultural context within the religious realm. Often, sacred works are mass-produced, stripped of their spiritual meaning, and repackaged as souvenirs to be sold.

Furthermore, younger generations of artists may have limited access to authentic training or be discouraged from pursuing creative careers altogether, especially under the pressures of capitalism. Establishing and maintaining the necessary spiritual discipline and years of apprenticeship is bordering on unfathomable in a world driven by profit and speed. Throughout Nepal, Tibet, and the diaspora, there are individuals, including artists, scholars, and spiritual leaders, committed to recognizing, preserving, and sustaining these sacred traditions. Art schools, monasteries, and cultural organizations are actively reviving interest in authentic methods for creating Paubha and Thangkas through workshops, exhibitions, and online opportunities.

By supporting local artists, learning about the cultural meanings behind their work, and considering the sacred context of these paintings, we can help sustain living traditions. Attending exhibitions, making informed consumer choices to purchase from ethical sources, and supporting educational initiatives are small yet active ways one can help; however, there is no shortage of opportunities for our efforts.

Conclusion: A Shared Language of the Sacred

While Paubha and Thangka originated in different countries, Nepal, Tibet, and were influenced by various traditions and cultures, at their very heart, they share the same sacred language, a language not of words, but of form, hue, devotion, and significance that transcends borders and is rooted in mindfulness, faith, and divine connection. These sacred paintings are not just aesthetic objects to behold; they are portals for transformation, both for the creator and for the observer. For the artist, the painting process is a spiritual act of practice, with each brushstroke serving as an offering, and each symbol functioning visually as a mantra. For the viewer, they are visual meditations, a reminder of the divine presence that surrounds us. In their silence, their faith, discipline, inner peace, and transcendence are self-evident.

In today's world, with our culture-driven society, commodified spiritual practices, and the looming threat of traditional knowledge erasure, considering the deeply rooted culture and intended spiritual orientation behind Paubha and Thangka is now more crucial than ever. These are not just "Himalayan artworks" to appreciate; they are living traditions, sacred inheritances that continue to change and grow, but only if we are willing to look and feel beyond the surface.

Explore more Paubha and Thangka artworks at Evamratna, where tradition meets timeless devotion.