A Living Legacy of Myth, Devotion, and Buddhist Art in the Heart of Patan

Kwa Baha, one of the preeminent and holy monastic complexes in Nepal, located along the city's north-south axis, near the historical Kwālakhu intersection, lies in the heart of Patan (Lalitpur). Typically called the Golden Temple for its brilliantly gliding rooftops and bright copper repoussé, Kwa Baha is formally known as Hiranyavarna Mahavihara, meaning "Golden Great Monastery" in Sanskrit. Kwa Baha is not merely an architectural wonder, but an active space that embodies the unique energy of spirituality, the genius of artistic engagement, or the richness of Nepalese Buddhist cultural practice. It exists and operates as a living monument, remaining a sacred site of lay devotion, a site of tantric practice, and a site of collective heritage. It is not merely a footnote on a traveler's itinerary, but a part of the identity of the people, specifically the Newar Buddhist community in the Kathmandu Valley.

Kwa Baha: A Temple of Legend and Light

The temple in the heart of Patan, Nepal, is hidden among the lanes, complete with historical, mythical, and silent amazement. Kwa Baha, also known as the Golden Temple. According to local folklore, an ancient Bihar that had collapsed from disuse lay covered with debris. The farmers digging on the land came across the talking image of Buddha. Even when they attempted to fix it in some observance or other, the image rejected the residence that King Bhaskar Dev had offered in its honor. Finally, the image gave rise to an odd request; it would only live in a place where nature had taken an unnatural turn, where mice chased cats. One day, the king saw a golden mouse chasing a cat. He interpreted this as the divine mark and immediately built the Golden Baha. The temple is believed to have been established around the 11th century and remains an active place of worship and culture. Even now, mice are not considered pests inside their walls. Instead, they are venerated as spiritual confidants of Kwāpādyo, or the Sakyamuni Buddha, and are accepted as part of the temple's spiritual heritage.

The memories of that long-forgotten miracle survived in every corner of Kwa Baha. It is a place of myth and devotion, of the meeting of the largest entities with the smallest creatures in the development of the story of light and devotion.

A Place of Worship and Creation

(Photo From Adobe Stock)

Although Kwa Baha is no longer a functioning monastery, it remains a center of lay Buddhist devotion. Its courtyard is filled with sacred objects, chaityas (or stupas), and shrines, some of which are ancient but all deeply devotional. The gold and copper-gilt roofs and ornately decorated shrines explain why this temple is popularly called the Golden Temple. When sunlight hits the gold and copper surfaces, the entire complex radiates divine illumination.

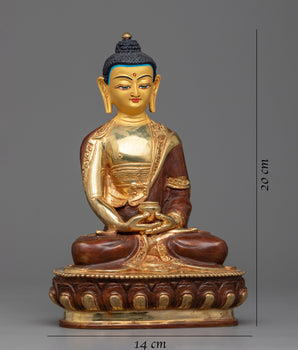

In the center of the temple is the kwapadyo, an image of Sakyamuni Buddha, placed inside a pagoda-style three-tiered temple. The Buddha is made from silver, is cast in an earth-touching gesture (bhūmisparśa mudrā), and wears elaborate sambhogakāya ornaments, torans, and figures of guardians.

The Bafacha: The Sacred Child Custodian of Kwa Baha

The centerpiece of Kwa Baha's living tradition is the Bafacha, a young boy selected from the Newar Buddhist community to serve as the caretaker of the temple deity for a limited time, always up to one month. The Bafacha, although given the title "little boy,” wears monastic robes, occupies the space of the temple, and acts with a strict ritualized conduct as he performs daily offerings, rings the temple bell, and assists with sacred rituals by taking on duties associated with the sacred. Most notably, the Bafachā symbolizes purity and devotion. While he is in a position, he is concurrently respected and venerated in the community because a pure-hearted child represents a spirit or being charged with spirituality closest to the divine.

This practice assumes that only a child of pure heart can maintain the fragile lining of rites and relationships within the temple. Maha Sangha has layered meaning and defines implications of community, lineage, and sacred service, embodied in the annual Bafacha tradition.

Historical Significance and Inscriptions

Kwa Baha holds a pivotal position in the religious and cultural history of the Kathmandu Valley. It's the golden age of flourishing, the Malla period (12th-18th century), when kings, nobles, and wealthy patrons funded its development. Their statements of devotion are inscribed in stone and metal throughout the temple complex, including donations of land, images, ritual items, and architecture.

These inscriptions not only open a window into the history of the temple's development but also provide insight into the socio-religious life of medieval Patan, highlighting the inseparability of royal support and Buddhist practice.

Over the subsequent centuries, Kwa Baha moved beyond its original courtyard. By establishing a series of associated shrines and satellite monasteries around Patan, it developed as a spiritual force in the city. Today, it is the home of the largest sangha (Buddhist monastic community) of all the Bahas (courtyard monasteries) in the Nepal Mandal, and it is central to the festivals, teachings, and community life of these monks.

Kwa Baha is a place of worship and a living testament to Nepal’s Buddhist heritage; its walls, statues, and inscriptions tell the stories of faith, artistic vision, and endurance.

Exploring the Courtyard: Art and Architecture

1. The Entrance: The main entrance is known as the Door of Bhairab, and it features a luxurious-looking toran that carries the seven Tathagata images. This is followed by another toran above the gatehouse, depicting Mahavajrasattva, Manjushri Dharmadhatu Vagisvari, and the six Buddhas of his mandala, adorned with an abundance of ever-present tantric symbolism.

2. Main Mandir: The three-story, massive shrine is adorned with gilded copper repoussé, depicting the deity of Singhanada Lokeshwor on a lion and an elephant.The five-buddha motif is also present on the torans, windows, and roof struts, which symbolize order in the world.

3. Swayambhu Chaitya: The central shrine, located within the courtyard, is a self-emerged stupa (swayambhū chaitya) within itself, the ancestral deity of the sangha of Kwa Baha. It is also decorated with gold repoussé, featuring lotus finials and banners.

4. Shrines and guardians: The shrines feature a multitude of sacred beings, including Tara, Hanuman, Vajrasattva, and Padmapani, some of which date back to the 9th century. The sacred symbolism of the temple can be traced to the use of mythical beasts, such as turtles, elephants, and leopards.

Tibetan Influences and the Gumba

Kwa Baha is a site of Newar Buddhism, but is also one of the few spaces that unite Himalayan traditions. Although Newar Buddhism was established autonomously, it nonetheless acquired some Tibetan influence, in part due to Newar merchants who would travel to Tibet and come back with riches, sacred rituals, teaching, and art forms.

One of the key figures in the blend of Tibetan and Newar Buddhism was Kyanchi Lama, a well-respected yogi from Kham, eastern Tibet. In the 1940s, he trekked to Patan, prostrating himself before the deity. Upon his arrival, he settled into Kwa Baha where he commercially set up a Gumba, or Tibetan-style assembly hall, on the temple grounds.

This Gumba has an image representing Amoghapasa Lokeshwor, one of the compassionate forms of Avalokiteshvara. There is also a wall of pictures of Kyanchi Lama to commemorate him. Today, Newar monks trained in the Tibetan tradition continue to do rituals here on behalf of Kyanchi Lama's patron lineage.

The Gumba or Gompa represents the combination of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism that breaks down the cultural barriers between Newar and Tibetan cultures. Adding to Kwa Baha's spiritual identity as a temple of shared practice, lineage, and living tradition.

Tantric Mysticism and Secret Shrines

Kwa Baha is not only a public place of worship; it is the center for practitioners of Tantric Buddhism. There are a few secret shrines, both within the bounded courtyard and behind it, that are only accessible to initiates:

- Agamche: the southeastern side of the temple has a tantric chamber with the deities Jogambar and his consort Jnanadakini. Within the chamber is Vajra Jogini/Basundhara.

- Ila Nani Courtyard: located behind the main complex, there is a second courtyard with two floors of prominent tantric icons. On the ground floor, there is Chandamaharoṣan (Achala), commonly known as Sankata, and on the upper floor, Chakrasambara is depicted in union with Vajra Jogini.

Festivals and Community Life

Kwa Baha is certainly a center of worship and artistic marvel; it is also the beating heart of a living community. Year in and year out, the monastery is home to a rich calendar of Buddhist festivals, ritual experiences, and public celebrations that connect and reconnect the local sangha. One of these important dates is the Gunla festival, the sacred month of Newar Buddhists, where, every morning at dawn, there is a procession, music, and ritual offerings in the courtyard.

Samyak Mahadana, one of the most significant forms of Buddhist almsgiving in the Kathmandu Valley, is one of 12 recurring events. Deities of Kwa Baha are curated into public view to be revered along with other deities from different Baha and Baha. These irreplaceable experiences unite generations of practitioners, from the elders chanting ancient scriptures to young children giving flowers, validating that the temple is the focal point of collective faith. The open courtyard of Kwa Baha takes the place of communal teaching, art conservation, or monastic education that connects sacred ritual acts to social plasticity. Therefore, the life they hold together is beyond a tired monument, but rather an accurate reflection of their present-day identities.

A Living Monument of Devotion

Kwa Baha, is far more than a historical temple; it is a place of worship and a vibrant, active embodiment of spiritual life. Daily rites are performed at the feet of ancient inscriptions as hundreds of years old statues gaze upon the worshippers' prayers, as worshippers express devotion through living ritual. Kwa Bahā expresses devotion not in quiet reverie but alive and constant practice.

The temple represents the wonderful convergence of myth, architecture, Newar, Tibetan, antiquity, of tantric and lay traditions. About other places of worship worldwide, the crossroad of the cultural and spiritual pathway is exceptional, which positions Kwa Bahā as a generative site, rather than a site of absence. A pilgrim looking for blessings, a scholar looking for its history, or an admirer of any sacred art, an experience at Kwa Bahā cannot be more immediate and timeless. The stupa is an embodied example of Nepal's Buddhist tradition, full of meaning, mystery, and luminosity.

Conclusion

Kwa Baha is not only one of the treasures of Patan, but it is also an ageless reflection of Nepal's Buddhist identity at a particular moment in history. The temple has a mythical origin, splendidly gilded roofs, and endless flickering butter lamps moved by the reverential practice with which they are kindled before the tantric deities of the temple. Each part of the temple has a continuity of attention, effort, devotion, beauty, and spiritual resistance or resilience. There are different layers of meaning as well: a dwelling place of a sacred legend, a gallery of Nepalese sacred art, a meeting point between Tibetan and Newar contexts, and a setting for both esoteric and public practice. Kwa Baha continues to advance not as a remnant of a previous era but as an active or living tradition that is now grounded in continuity and carrying tremendous meaning.

To encounter Kwa Baha is to step into another dimension of reality where the past and present work together; where golden light, whispers, and scents of incense all point to lived and living legacy.