Introduction: Guardians of the Gate and the Mind

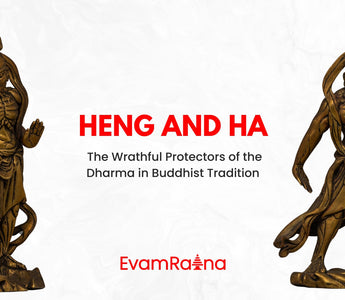

Every Buddhist temple frequenter recognizes the pair of guardians named Heng and Ha. Two solid statues stand in deadly martial postures in front of the temple gate as planet-born defendants. Heng's open mouth expresses silent anger through his face, matched by Ha's spiritual determination that anchors his sealed expression. Visitors remember the "Two Generals" under their alternative name of Heng Ha Erjiang (哼哈二将) due to their memorable appearance.

Both statues possess greater meaning than their role as temple protectors. The two celestial warriors draw their meaning from Buddhist mythology combined with Taoist legend and temple ritual. The stone guards protect sacred areas while representing cosmic powers, in addition to serving as psychological symbols that push practitioners to test their level of mental understanding. Though their physical appearance is powerful, their true purpose exists to transform.

In this blog, we will be looking at the deep-rooted origins of Heng and Ha, their symbolism, and why these timeless figures are still meaningful to Buddhist philosophy and modern-day spiritual life.

The Origins of Heng and Ha

The Indian Buddhist Roots: From Dvarapalas to Vajrapani

Temples in Indian Buddhist architecture used dvarapalas as temple guardians, which became the foundation for Heng and Ha figurines. The Sanskrit term "dvarapala" defines a temple guardian who protects entry doors by preventing evil forces and hostile energy. During the Buddhist entry into China, many of its original imagery merged with local worship traditions and artistic practices.

In the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, Vajrapani stands as the wrathful protector of the Buddha who wields a thunderbolt wand in two manifestations called Heng and Ha. Enlightened wisdom, along with the destructive force that silences ignorance, are the representations of Vajrapani.

Vajrapani's energy transformed through Chinese tradition into two guardian entities that became General Heng with his mouth sealed and General Ha showing his open mouth, yet similar to Japanese and Korean temple guardian pairs named "A-un."

Phonetics and Cosmology: The Sounds of the Universe

The sounds Heng and Ha serve as more than mere labels, as they contain spiritual importance for Vajrayana Buddhism. The sacred Sanskrit seed sound syllables "A" and "Hum" (also known as "Hung") exist in these names. According to Vajrayana Buddhism, many mantras and mudras contain these syllables, which symbolize complete existence.

-

"Ha" (A) – The open mouth symbolizes the starting point of everything, and it stands for creation’s origin and the origin of all things.

-

"Heng" (Hum) – The closed mouth conveys both termination and silent dissolution along with death.

The arrangement symbolizes samsara, also known as the cycle of birth and death that reveals an essential cosmic truth about how everything originates and ends in the cosmic breath. The four sonic elements unite to produce the sacred term "Aum" or "Om," which stands as the basic audio of universal existence and cosmic reality.

Heng and Ha in Chinese Buddhist Temples

Temple Architecture and Symbolic Placement

Heng and Ha serve as more than temple decorations because their position at entrances represents deep traditions running through centuries of practice. These statues observe visitors at the Shanmen, which serves as the official entrance that defines Chinese Buddhist temples. The gate functions as a transcendent area that defines the threshold between material life and spiritual realities. Devotees undertake an inner spiritual odyssey after passing through the Shanmen because this gateway symbolically removes them from external life disturbances to access stillness and mindfulness, as well as spiritual awakening. With Heng and Ha present, individuals reveal they should not underestimate the seriousness of advancement. Their role extends beyond protection into initiation since these guardians test spiritual seekers during their threshold crossing using both purpose and mental alertness.

The placement of Heng and Ha on the left and right side (when viewed by an entering person) symbolizes a strength of opposition, which demonstrates fundamental Buddhist doctrine. Sound breath energy manifests through open-mouth Heng, but completion and relaxation appear through standing Ha with his mouth closed. The postures of these statues illustrate the continuous relationship between contemplative thinking and taking action as well as between meditation and outward practice. The artistic representation demonstrates the philosophical dualism of form and emptiness because it shows how all material existence contains no true self-nature. The passage through guardian figures extends beyond the act of crossing an archway since it represents the philosophical Middle Way leading to the balanced path of wisdom taught by the Buddha.

Entering a temple implies both physical movement and spiritual development because of the transformational ritual it initiates. The transformation towards enlightenment has Heng and Ha serving as its sentinels, who show us that self-awakening starts when we purposefully escape false beliefs to discover the path of truth. These guardians push visitors to consider if they stand ready to embark on the pilgrimage, both physically and mentally.

Not Just Statues: Psychological Archetypes

Heng and Ha function as spiritual metaphors for Buddhist discipleship, while they also exist as protective temple guardians harboring temple entrances. The statues demonstrate the practice of mental control, which protects minds from undesirable mental elements, including thoughts and impulses that creators regard as impure. The boundary protection service of these guardians matches the role of maintaining the protected state of aware mental space. Discipline in Buddhist teachings focuses on creating mindfulness as well as the ability to discern beneficial thoughts from those that derail spiritual progress.

Right intention forms a vital element of the Noble Eightfold Path since it manifests through the Buddha images. Their solid stances show a strong dedication to staying focused on compassion, together with truth and moral conduct, even in the face of ego and temptations. They demonstrate through their lifetime example that the path of liberation requires purposeful determination, which must be developed with daily dedication.

Heng and Ha powerfully display wrathful compassion through their fighting forms, which show that compassion can present itself as a powerful force beyond softheadedness. While guarding the Buddhist teachings and their followers sometimes demands both protective power and fierce temperament, Heng and Ha demonstrate this through their combative appearances. The divine power that manifests wrath does so from deep, enlightened love that stands respectfully to take action against ignorance and harm. Heng and Ha represent spiritual forces that guide the soul to combine compassionate love with active bravery.

Mythological Interpretations

From Vajrapani to Chinese Generals

Chinese adaptations depict General Heng as Narayana Vajra, whereas Ha resembles Guhyapada Vajra, who possesses the role of Vajra Warrior of Secret Signs. Through time, human forms completed the transformation into anthropomorphic beings, which later became part of Chinese mythology.

During the Ming Dynasty, when the authors wrote Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen Yanyi), they transformed Heng and Ha into supernatural generals named Zheng Lun and Chen Qi:

-

Zheng Lun (Heng): Has the power to suck out souls using jets of white energy from his nostrils.

-

Chen Qi (Ha): Can bind enemies with yellow energy from his breath.

The fictionalized version of this literary adaptation played a major role in shaping how Chinese culture viewed the Heng-Ha duo throughout the nation.

Integration into Taoist and Folk Traditions

Both Heng and Ha encountered a similar phenomenon of religious boundary transition as other East Asian religious figures. The gods were integrated into Taoism practices until they became known as Door Gods, which people used during Chinese New Year and other festivals by presenting or painting them on household gates for misfortune protection and beneficial energy attraction.

People gradually interpreted their two distinctive variations spiritually and philosophically. These two beings within Taoism, along with Confucian traditions, represented the essential quest for maintaining equilibrium between active behavior and self-restraint and vocal power and contemplative silence.

The Nio Connection: Heng and Ha in Japanese Buddhism

Agyō and Ungyō: Their Japanese Counterparts

Within Japanese tradition, the Nio statues known as Kongōrikishi match the pair of Heng and Ha. These names originate from the Sanskrit language through phonetic translation:

-

Agyō (阿形): Mouth open, vocalizing "Ah" represents birth while displaying overt strength as the origin of everything which exists.

-

Ungyō (吽形): Mouth closed, uttering "Un" (or "Hum") expresses the three meanings of passing away, internal capacity, and complete depletion.

The guardian figures complete their appearance at temple entrances throughout Japanese Buddhism exactly as they do in Chinese temples. The status of these complex figures displays forceful poses alongside exact visual representation of eyes and veins so that they will scare away evil forces while also creating deep respect among the religious followers. The statues of Nio have achieved status as traditional masterpieces in Japanese temple construction.

Cultural Continuity and Shared Symbolism

The core meaning of Heng and Ha remains steady throughout East Asian regions, regardless of the varying artistic approaches and cultural manifestations between Heng and Ha. Across China, they are named Heng and Ha, while Japan calls them Agyō and Ungyō, and Korean temples use fellow guardian statues in their gateways. The essential body posture with one figure displaying an open mouth and the other displaying a closed mouth represents sacred syllables connected to the beginning and end of all things. The sounds originating from the Sanskrit naming "A" and "Hum" represent more than mere phonetic oddities since they exemplify universal dualistic principles of creation and destruction along with vocal expression and silence, movement, and fixity.

The pair of guardians guard both physical manifestations as well as spiritual entities. These symbols guard temple entrances as they serve dual purposes of protecting sacred places from external threats and helping believers make an inner passage between everyday living and spiritual practice. The ritual passing between the gatekeepers represents a deeper than physical transition which leads individuals from ignorant states to wise states, alongside a change from worldly thoughts to deep spiritual clarity. The practitioner remembers that awakening requires complete alertness through the wisdom embodied by statues' powerful expressions and stable positions.

What makes Buddhism's presence in all cultures so enduring is Buddhism's adaptive yet sedimented nature. As the Dharma travelled across Asia, it met different beliefs, languages, art forms, and many other things. Buddhism has never said that it must adhere exclusively to one or the other, but absorbs and reframes them, ultimately instilling its teachings in new symbols without losing its core essence. The continuance of the image of Heng and Ha — however they're named or celebrated — is the balancing act of continuity mixed with cultural change. They are more than just guardians of temples; they are living evidence that Buddhism speaks many different languages, yet strongly and simply one unified voice.

Artistic and Iconographic Features of Heng and Ha

Appearance and Attributes

Heng and Ha are typically represented as:

-

Heavily muscular warriors, either bare-skinned or armor-clad warriors.

-

Wearing military skirts, a waist sash, and boots.

-

Bearing vajras (thunderbolt clubs) — symbols of unbreakability and spiritual power.

-

Posed in aggressive stances or defensive martial positions.

-

Often stomping on demons or evil spirits, reminding one of the triumph of Dharma over delusion.

Their visage shows raw fury, flaring nostrils, threatening snarls, and fierce eyes. Their wrath is not uncontrolled screaming violence; their fury is protective, channelled protective rage; a "just rage" only to ignorance and disturbance.

Symbolism Beyond the Physical

The iconography is highly symbolic:

-

Raised fists and open palms represent engagement and awareness.

-

Muscled bodies signify courage and spiritual strength.

-

The vajra, as a ritual object, pierces attachment to illusion and dualistic thinking.

-

Their duality — one open, one closed — suggests the yin-yang harmony that sustains Chinese cosmology.

The Spiritual Role of Heng and Ha

Guardians of the Temple — and the Mind

Heng and Ha are guardians of the entrances to temples as well as the practical role of spiritual bouncers, keeping undesirable and evil forces out of the temple grounds. However, from a more deeply determined meditative perspective, they are also guardians of our internal temple, which can be represented by the heart and mind.

In this context, they represent:

-

Mindfulness: the essential and watchful awareness needed to observe harmful thoughts and interrupt their compulsion

-

Right Effort: consciously choosing to maintain the purity of one's practice.

-

Unshakeable resolve: required to continue to follow the Eightfold Path.

They are reminders that spiritual life is not always gentle and tranquil; sometimes it requires a ferocity of spirit to uproot delusion.

Wrathful Deities in Vajrayana and Esoteric Buddhism

Within esoteric traditions of Buddhism, such as Tibetan Vajrayana, wrathful deities are not seen as evil but rather fierce expressions of enlightened compassion. Heng and Ha can be understood as wrathful manifestations of protective compassion — their rage is not egoic but protective: its purpose is to dispel attachments and egoic illusions through shuddering annoyance.

Lessons from Heng and Ha for Modern Practitioners

A few teachings from Heng and Ha for practitioners in the modern period:

1. Guard Your Inner Gate

Just as they guard the gates to temples, we must protect the gates to our senses — how we allow things into our mind, heart, and spirit. As we are discovering in this tradition, discipline, vigilance, and awareness are our primary tools as we inhabit the path.

2. Embody Strength with Compassion

Wrathful singularity is fierce but never unkind. In a time of moral ambiguity, standing your ground in truth is not violent but simply kind, even when that means it will be expressed strongly.

3. Accept the Cycles of Life

The "A" and "Hum" sounds, beginnings, and endings, reinforce our learning that impermanence is not something to be feared but a powerful teacher in the manifestation of life. Living at peace is learning to flow with the cycles, not against them.

Conclusion: Eternal Guardians of Awakening

Initially, Heng and Ha present as powerful, if somewhat threatening, guardians---frozen statues in mid-whoop, left over from a mythical time. But the depth of their importance in Buddhism runs much deeper than what their physical presence suggests. They are living symbols that represent eternal truths, that resonate as powerfully now as they did hundreds of years ago. They stand at the entrance of sacred space, delineating a crucial transition, not only from the secular world to the temple grounds, but from unawareness to awareness, distraction to focus.

Through their open and closed mouths, they pronounce primordial syllables, the sound of the universe, and the silence that is possible following. They are sound and silence, action and reflection, form and emptiness. These contrasting aspects of nature remind us that real understanding does not come from extremes, but rather from the balance of both. Heng and Ha do not just stand there; they speak, if you care to listen. They present an invitation to meet yourself, to put down all that does not serve you now on your path, and move forward mindfully and bravely.

Heng and Ha signify more than myth; they signify more than art; they are a call to awareness. They ask us to protect our own inner temple like they protect the sacred lands they inhabit. In a modern world full of distraction, noise, and spiritual confusion, they are a bold reminder that we must make a conscious decision to begin each step toward truth: a decision to cross the threshold with first discipline, then intention, then fierce compassion. In them, we recognize these loud and deafening guardians can also quietly convey the deepest truths.